A. Philip Randolph's 1963 Speech

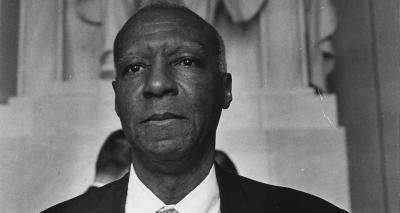

Photo by Rowland Scherman, U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service / Public Domain

A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, stands in front of the Lincoln Memorial, August 28, 1963

On a hot August day in 1963, A. Philip Randolph came to the podium following a prayer by Reverend Patrick O’Boyle, the Archbishop of Washington. The fact that the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom gathered a quarter of a million people, was a tribute to his skill as an organizer. This was not the first time that he planned a massive protest in Washington, DC. In 1941 he was already an established civil rights leader when he organized a mass march to protest the racism in government policies that excluded Blacks from defense jobs and New Deal programs.

He had probably already prepared his speech in 1941 when the march was called off. President Franklin D. Roosevelt met his demands, so there was no need for a protest. The President issued an executive order that all charges of racial discrimination would be investigated by the newly established Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC).

In May of 1957, Randolph organized a gathering at the Lincoln Memorial to call on the federal government to proceed vigorously with enforcing the integration of schools in accordance with the Supreme Court’s Brown v Board of Education ruling. This time Dwight D. Eisenhower was President. He did not take immediate action, but the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was already being discussed in Congress and Eisenhower was lobbying against Democrats’ attempt to weaken the bill. It was passed in September and signed by the President. This was the first civil rights law passed by Congress since 1875. It established the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department so that the mechanism was in place to prosecute civil rights cases, specifically interference with the right to vote.

Randolph’s genius as an organizer resulted in combining his idea of a march for jobs with Martin Luther King’s hopes to have a march for freedom. This time the President, John F. Kennedy, took a keen interest in the march. He met with the leaders and at first discouraged them from having the march while civil rights legislation was pending in Congress. Then the President discouraged the leaders because he said he had concerns about security and the potential for violence. Finally, it was clear that Randolph, King, and others were determined. Then Kennedy endorsed the march and made preparations for security.

Even in the final hours before the speeches started at the Lincoln Memorial, Randolph’s skills as an organizer and his long experience were called upon again. Questions were raised about the content of John Lewis’s prepared speech. Some participants even threatened to withdraw at the last minute. But Randolph and King convinced Lewis to make changes to his speech. And the program proceeded.

While the march is largely remembered because King went off script and repeated part of his stump speech about having a dream, Randolph presented context for the march, the political philosophy behind the struggle for civil rights, and a plan for the future.

Randolph pointed out that segregation, oppression, and exploitation occur all across America as they do today. It was from these places that people had gathered. He said,

“We are the advanced guard of a massive, moral revolution for jobs and freedom. This revolution reverberates throughout the land touching every city, every town, every village where black men are segregated, oppressed and exploited.”

Then he made it clear that the struggle for jobs and freedom is more than civil rights. Like 59 years ago, America faces challenges including women’s rights, economic injustice and inequity, LGBT+ rights, reparations and justice for Native Americans, plans for welcoming and supporting immigrants, and gun violence. The list goes on. As Randolph said,

“But this civil rights revolution is not confined to the Negro, nor is it confined to civil rights for our white allies know that they cannot be free while we are not.”

He reminded the crowd that many changes are required. “Now we know that real freedom will require many changes in the nation’s political and social philosophies and institutions.” Then he explained the political philosophy that will support the necessary changes: “The sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of the human personality.”

These are important words for today. The sanctity of private property is still the foundation of our economic policies, and it is also the unspoken foundation of the distribution of power.

Sadly, the 21st century has seen changes in the institutions of government and the economy that increase the sanctity of private property at the expense of the sanctity of the human personality. Economic inequity has reached levels today that were unimaginable in 1963.

In 2010 the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United that corporations are protected like individuals by the First Amendment. Corporations are free to use their accumulated property to spend it on influencing elections. In other words, to advance the interests of private property. More recently, state governments are enacting laws intended to make it more difficult for people of color to vote. All of this is intended to preserve the priority of the sanctity of property.

Without using the word slavery, Randolph explains that the inflated priority of property is left over from when Black people were treated as property. The idea that a person can be considered property required that institutions protect the interests of property over the interests of human beings. He explains, “Negroes are in the forefront of today’s movement for social and racial justice because we know we cannot expect the realization of our aspirations through the same old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies that have all along frustrated our aspirations.”

Because we have not addressed the institutional and structural foundations designed to justify slavery, we have unfinished work ahead of us to create a society that is not based on the “old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies.”

Randolph condemned those who “are more concerned with easing racial tensions than enforcing racial democracy.” He talked about supporting federal legislation, and marching in the streets. But his final challenge to those gathered was:

“When we leave, it will be to carry on the civil rights revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land.”

That challenge is as relevant today as it was in 1963.

A recording of A. Philip Randolph’s speech is available in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Part 6 of 17 broadcast by the Educational Radio Network / ERN's coverage of August 28, 1963 on the Open Vault WGBH Archives website.