Septima Poinsette Clark

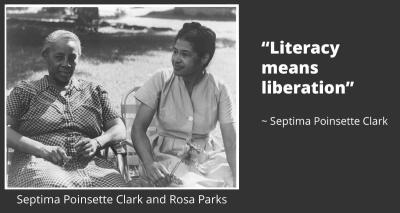

Photo by Ida Berman / Visual Materials from the Rosa Parks Papers, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (023.00.00)

Septima Clark and Rosa Parks at Highlander Folk School, Monteagle, Tennessee, 1955, where Clark initially designed and taught Citizenship Schools.

“Septima Poinsette Clark’s gift to the Civil Rights Movement was education.”

~ from the description of “Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark” by Katherine Mellen Charron

Septima Poinsette Clark (1898-1987) was a consequential African American educator and civil rights activist.

She is best known for designing education programs and developing Citizenship Schools throughout the southern U.S. The Citizenship Schools provided instruction to African Americans in adult literacy, political and economic literacy, voter registration, political parties, local school boards, taxes, and social security. They empowered people to register to vote, access their legal rights, and gain resources to improve their communities.

“Clark’s teaching practice successfully bridged the divide between individuals and the national movement by connecting people’s everyday struggles under racism to the larger issues of structural inequality and discrimination.”

“Citizenship schools molded everyday people into leaders in their own right.”

~ from Women in the Civil Rights Movement Historic Context Statement

Between 1957 and 1970, more than 28,000 African Americans attended these schools and workshops including activists such as Rosa Parks, who attended just a few months before she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man, which led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott; and Diane Nash, a civil rights leader who was involved in integrating lunch counters through sit-ins, the Freedom Riders, and the Selma Voting Rights Campaign.

“I don’t think that in a community I need to go down to city hall and talk; I think I train the people in that community to do their own talking.”

~ Septima Poinsette Clark in Charron, K. M., & Cline, D. P. (2010). “I train people to do their own talking” Septima Clark and women in the Civil Rights Movement from interviews by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and Eugene P. Walker. Southern Cultures, 16(2), 31-52, p. 48.

This groundbreaking education program was first sponsored by the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee and later the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

“Connecting grassroots education to grassroots activism, the program played a crucial role in galvanizing people to participate in the civil rights movement.”

~ from Local and National Leader: Septima P. Clark, Remembering Individuals, Remembering Communities: Septima P. Clark and Public History in Charleston on the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative website

Family life

Clark was was born on May 3, 1898 and raised in Charleston, South Carolina.

Her father, Peter Porcher Poinsette, was born into slavery on the plantation of Joel Poinsette. After the Civil War he held a variety of jobs including working for Clyde Line Steamship Company, and later as a waiter and a custodian, and he briefly owned a lunchroom.

Her mother, Victoria Warren Anderson, was born free in Charleston and learned how to read and write while living with family in Haiti. After her marriage to Peter, she worked from home as a laundrywoman. This gave her more control over her time as they raised their growing family.

Both parents strongly supported the education of their eight children.

She married Nerie David Clark, a navy cook, in 1920 and they had two children: a daughter, Victoria Irma, who died just 23 days after birth in 1921, and a son, Nerie David Clark Jr., born in 1925. Just 10 months later, Clark’s husband died later of kidney failure.

Teaching and activism

Clark’s teaching career began in 1916 after she graduated from Avery Normal Institute, the first accredited secondary school for African Americans in Charleston, and received her teaching certificate. African Americans were not allowed to teach in the Charleston public schools at the time so Clark taught for several years at a one-room, all-black school on Johns Island, South Carolina, a place she returned to several times.

“Septima Clark’s method of teaching was very innovative, it was progressive, and it was ahead of its time, and she learned this method from Johns Island. And that is essentially meeting her students where her students were. But also treating her students, particularly adult students, with tremendous respect.“

~ Jon Hale, Associate Professor of History, College of Charleston in “Biographic video about the life and work of Septima P. Clark,” South Carolina Hall of Fame, 2014, courtesy of SCETV on The Voice of Septima P. Clark

Clark started her activist career in 1919 by joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to advocate for a law to end legal segregation against Black teachers. The campaign was successful and in 1920 Black teachers gained the right to teach Black children at public schools in Charleston. She continued to be active in the NAACP, fighting for equal pay and rights for Black workers and, in the 1950s, for the integration of public schools.

Clark continued teaching in both rural and urban communities throughout South Carolina: Johns Island, the Avery Normal Institute, and public schools in Columbia and Charleston.

She also pursued her own education, spending summers at Columbia University in New York City and with the renowned historian W.E.B. Du Bois at Atlanta University in Georgia. She earned a B.A. from Benedict College in Columbia in 1942 and an M.A. from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1946.

In 1956, South Carolina passed a law that prohibited city and state employees from belonging to civil rights organizations. Clark refused to resign from the NAACP and after 40 years of teaching, the school board fired her and she lost her pension.

Highlander and Citizenship Schools

Clark had attended a workshop in 1954 on school integration at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, founded by social activist Myles Horton. Highlander was an integrated, grass roots education center dedicated to social justice.

“[Highlander] operated on the philosophy that oppressed people know the answers to their own problems.”

“Septima Clark believed that the most important thing was to develop local leaders, people in their communities who could assume a leading role in getting things done and solving community problems, and she was concerned with developing women, in particular, as leaders.”

~ Katherine Mellon Charron, author of “Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark” in “Biographic video about the life and work of Septima P. Clark,” South Carolina Hall of Fame, 2014, courtesy of SCETV on The Voice of Septima P. Clark

Her participation at Highlander “pushed Clark to translate adult education theory into political and community action” says Katherine Mellen Charron (“Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark.” University of North Carolina Press, 2009, pg. 217).

Clark developed the workshops at Highlander into Citizenship Schools teaching literacy, voter and civil rights, and activism. She inspired people to have pride in their culture and firmly believed that education is key to economic and political empowerment. In 1956 Clark joined Highlander’s staff full time as Director of Workshops and in 1957 became Director of Education, designing and overseeing the Citizenship School program.

Clark encouraged Esau Jenkins, a Johns Island farmer and bus driver, to come to workshops at Highlander.

“Taking what he had learned from Highlander, Jenkins... began a literacy effort on the bus he used to take tobacco workers and longshoremen to Charleston. With a seed grant from Highlander, Jenkins took this ‘rolling school’ to the back of a grocery store on the island, which hid the school from the white community’s gaze.”

“By 1961, 37 Citizenship Schools had been established on the Sea Islands and nearby mainland. These students went on to start a low-income housing project, credit union, nursing home, and more within their communities.”

~ from Septima Clark, SNCC Digital Gateway, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Legacy Project and Duke University

Southern Christian Leadership Conference Citizenship Education Program

When the state of Tennessee forcibly closed Highlander in 1961, the education program and funding for it was transferred to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

SCLC established the Citizenship Education Program (CEP), modeled on Clark’s Citizenship Schools. Dorothy Cotton was SCLC’s Director of Education and Clark served as Supervisor of the Teacher Training Program. She developed curriculum, led teacher training, and over 800 Citizenship Schools were created under her leadership.

“We used the election laws of that particular state to teach the reading. We used the amount of fertilizer and the amount of seeds to teach the arithmetic, how much they would pay for it and the like. We did some political work by having them to find out about the kind of government that they had in their particular community. And these were the things that we taught them when they went back home. Each state had to have its own particular reading, because each state had different requirements for the election laws.”

~ Septima Poinsette Clark in Oral History Interview with Septima Poinsette Clark, July 30, 1976. Interview G-0017

Martin Luther King Jr. worked with Septima Poinsette Clark and called her the “Mother of the Movement.”

King so appreciated her contributions, she was one of the few people he invited to travel with him to Oslo, Norway when he accepted his Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

“Septima Clark bridged the gap between SNCC and an older generation in a way that few did, and her lifelong work in adult literacy and citizenship education helped pave the way for SNCC’s organizing work, especially the Freedom Schools of Mississippi.”

~ from Septima Clark, SNCC Digital Gateway, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Legacy Project and Duke University

After Clark retired from SCLC in 1970 she continued to be active in the struggle for civil rights, focusing on “...education and politics, black children, care for the elderly, and women’s issues. In 1972, she won election to the Charleston County School Board, the same body that had fired her for belonging to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sixteen years earlier. As the lone African American and first woman on the board, Clark promoted improvements for teachers and students and tried to ensure that African Americans had a representative place in the curriculum.” (Charron, Katherine Mellen. “Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark,” University of North Carolina Press, 2009. pg 345.)

Clark won reinstatement of her teacher’s pension in 1976 after the governor of South Carolina declared she had been unjustly terminated in 1956. However, she did not receive full compensation at that time. In 1981, she finally received back pay from the state of South Carolina for eight lost work years.

Clark died December 15, 1987, at age 89, on Johns Island, South Carolina, where her teaching career began.

Awards and Recognition

- Woman of the Year by The Utility Club, Inc., for being an “illustrious citizen of the United States of America; champion and educatory; crusader for liberty, equality, security, justice, and peace; advocate of the better life for million now living and for generations yet unborn,” 1960

- Chatham County Crusade for Voters award Septima P. Clark "Affiliate of the Year" “for your brilliant leadership, courage, and dedication to the cause of freedom for Negro people. You have inspired and taught countless numbers of the culturally deprived all across the south giving them a true sense of dignity,” 1964

- Martin Luther King Jr. Award from SCLC for great service to humanity, 1970

- NACPE Achievement Award Committee on Social Justice, in grateful acknowledgement of her outstanding contributions to equality and social justice, 1975

- Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Social Change Certificate of Award in recognition of her commitment to the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence, 1976

- Charleston County Education Society’s Community Service Award, 1976

- H. Councill Trenholm Memorial Award, the National Education Association’s highest race relations honor, for leadership in the advancement of intergroup understanding within the education profession, 1976

- Honorary Degree of Letters, College of Charleston, 1978

- Living Legacy Award, presented by President Jimmy Carter, in recognition of a life of achievement, 1979

- Order of the Palmetto, South Carolina’s highest civilian honor for outstanding service, 1982

- American Book Award for “Ready from Within: Septima Clark and Civil Rights,” Clark's second autobiography, 1987 (Clark’s first autobiography, “Echo in My Soul,” was published in 1962)

- Drum Major for Justice Award, presented by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) at her funeral in 1987. The Reverend Joseph E. Lowery, president of SCLC said “her courageous and pioneering efforts in the area of citizenship education and interracial cooperation won her SCLC’s highest award, the Drum Major for Justice award.”

Sources

Charron, Katherine Mellen. Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark. University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Collier-Thomas, Bettye, and V. P. Franklin, eds. Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement. NYU Press, 2001.

Featherstone, Liza Clark, Septima 1898–1987. Contemporary Black Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

Clark, Septima Poinsette on the The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University website.

Remembering Individuals, Remembering Communities: Septima P. Clark and Public History in Charleston on the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative website, College of Charleston.

Septima P. Clark Papers, ca. 1910-ca. 1990, Avery Research Center on the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative website, College of Charleston.

Septima Clark, SNCC Digital Gateway, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Legacy Project and Duke University.

Septima Poinsette Clark on the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderbilt University "Who Speaks for the Negro?" website.

South Carolina Superheroes: Septima Poinsette Clark on the South Carolina State Museum website.

Giants Who Walked Among Us: Remembering Septima Clark, Ella Baker, and Dorothy Cotton on the Women AdvaNCe website.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. Septima Poinsette Clark. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Septima Poinsette Clark on The Biography.com website.

Septima Poinsette Clark and Eugene Walker in Oral History Interview with Septima Poinsette Clark, July 30, 1976. Interview G-0017. Documenting the American South, UNC.