The Slow Massacre: East Phillips and North Desha Counties, Arkansas: Then and Now

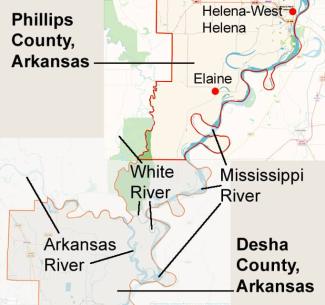

Map outlines from the Phillips County, Arkansas page in Wikipedia; county color shading and labels added by Cam Howard, Ending Racism USA.

How TIAA Purchased A Legacy of Racism and Murder

We are in a battle for the truth in the U.S., in the state of Arkansas, and here in Phillips County. In this moment, as in the past, the truth is being covered up.

First, a few points of geography and history:

Phillips County is in the Delta, one hundred miles south of Memphis, on the eastern side of Arkansas, up against the Mississippi River.

Maps of Phillips County and Desha County from OpenStreetMap. City markers and labels added by Cam Howard, Ending Racism USA

The county is surrounded by rivers in all directions. Elaine is in the center of the county, but Helena-West Helena is designated as the county seat. Phillips County has the highest percentage of Black residents in the state of Arkansas. For reference, it is only sixty miles from the town in Mississippi where Emmett Till was murdered in 1955.

South Phillips County and the northern part of Desha County are highly interconnected. North Desha County is cut off from the rest of Desha County by the rivers. Because of the flooding and constant shifting of the rivers, the soil here is very rich with sediment and is some of the best soil for growing crops. Yet the control of the land and water and labor has been the battle here at least since the Europeans first arrived.

The 1919 Massacre

On September 30 to October 2, 1919, at the end of the “Red Summer,” when many racially motivated murders and other forms of violence occurred around the country, in Phillips County, Arkansas, Black farmers organized a union to fight for full pay for ginning their cotton. In response, many hundreds of Black people were murdered by posses of white men; then federal troops were brought in, and instead of helping, they killed more Black people. These three days of slaughter have come to be known as the “Elaine Massacre.”

Following the Elaine Massacre, a committee of seven white planters, land owners from Helena, was formed to determine what had happened. No white people were arrested for these murders, while about two hundred Black people were arrested, and sham trials sent twelve of them to death row for the killing of a few white folks.

The NAACP sent journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells to Phillips County to document the massacre and its immediate aftermath. She wrote a report titled “The Arkansas Race Riot.” On appeal to the US Supreme Court, the Elaine Twelve were released. This horrifying massacre and its long aftermath have been investigated by many people. But the truth is still being covered up.

The Elaine Legacy Center (ELC) has been commemorating the Elaine Massacre of 1919 since 2012. A truth-seeking commission was held at ELC in 2019. Some people say there were only sharecroppers, or a small number of Black landowners, in Phillips County in 1919. Yet as Ida B. Wells herself notes in her early report, Paul Hall of the Elaine Twelve was himself a landowner. And the extended families of many more who were arrested were landowners. This is important not because sharecroppers and tenant farmers are less important than landowners, but because it is the truth, despite the story that has been molded, primarily by white people with money, land, and power in Phillips County. Their story erases the fact of Black land ownership prior to the massacre and subsequent land theft.

Oral history by Black families, the families of the descendants of the massacre’s victims and survivors, has kept the fuller story alive. Many of the same families who were here before the massacre, as both perpetrators and survivors, still have a presence here. I honor their bravery and thank them for sharing their stories with me. These families show strength and resilience to still be here sharing the stories of the time before, during, and after the massacre. Their truth matters.

Before the 1919 Massacre

By the 1800s, there had already been at least a thousand-year history of humans on this land, including a horrible Trail of Tears through this area and the removing of the Quapaws. Many folks here today claim ancestral connections with those peoples. There are still some remnants of the mound builders.

In 1860, almost 9,000 people were enslaved here, some by the ancestors of the same white families who continue to have power and control in Phillips County today. According to the 1870 census, after the Civil War, almost two hundred Black people owned land in Mississippi township of north Desha County around Snow Lake. In the part of Phillips County south of Elaine known as Mooney township, in 1900 there were twenty-seven Black landowners and twenty-eight white landowners.

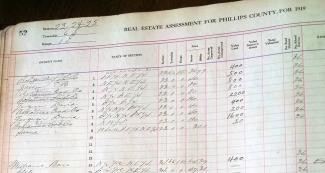

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Hadlock

Photo of Phillips County 1919 tax records showing the Fergusons as land-owners.

By 1910 in Mooney township, there were thirty-two Black landowners, including the Fergusons and the Martins. So, the number of Black landowners in Mooney was going up. During this time there were also many racially motivated violent incidents targeting Black people. Night riding and whitecapping were not uncommon.

As Richard Wright, the famous author who moved to Elaine as a child in 1916, wrote in “Black Boy,” “When we arrived in Elaine I saw that Aunt Maggie lived in a bungalow that had a fence around it and wild flowers grew. Aunt Maggie's husband, Silas Hoskins, owned a saloon. He had a horse and buggy … One morning Uncle Hoskins didn’t come home. Before dawn we were fleeing for our lives. I learned afterwards that Uncle Hoskins had been killed by whites who coveted his flourishing liquor business.”1

Today, some white people with money, still trying to control the narrative, say that the area of south Phillips County in 1919 was unsettled. But this doesn’t sound like an unsettled area to me. It doesn’t sound like all Black people there were sharecroppers. And it doesn’t sound like you would necessarily be the only one killed or arrested if white people wanted you gone; your family members could also be threatened as a consequence of your actions. If you spoke up, you might not be the person who received the “punishment.”

The Tulsa Massacre of 1921, we know, was a punishment for Black people having success. That was also true here in Phillips County, in the Elaine Massacre, which happened before Tulsa.

What Wealthy White Folks Had to Gain

The economic pressure in 1919 in Phillips County was intense. Many of the white male business and land owners, the planters and cotton factors of Helena, were trying to gain more power and wealth. Note that several of them would be chosen by the governor to be on the Committee of Seven after the massacre, trusted to find out what happened. This was a tangled web of conflicts of interest. It seems obvious why there is still so much confusion around what did happen in Phillips County in 1919.

In 1919, the Southern Alluvial Land Association was advertising to bring investment and attract white people to the Delta. Pamphlets were produced to market the area. The land was advertised as having an incalculable supply of pure sparkling artesian water under the ground. “Thousands of flowing wells are to be found. This artesian water has contributed to good drainage as much as good health.” The brochures claimed that one hundred different crops could be grown on the rich first seven inches of soil – immensely rich in lime, nitrogen, phosphorus – without any fertilizer. The ad explained that dams, levees, and drainage ditches had been built.2 Of course, we know that the white planters did not build the levees, ditches, or canals. Black people did.

In 1917, Congress passed a law to pay for levees, working through a structure of local levee boards. This led to the formation of numerous drainage districts and levee boards. Wealthy white landowners controlled these levee boards from the outset, and continue to today. Every landowner paid, and is still paying, a tax to them. And just as land can and could be sold for unpaid property taxes, land can and could be sold by the drainage districts and levee boards for unpaid fees. These forfeiture auctions were and are happening in the Arkansas Delta.

In July 1919, oil had been found nearby and leases for drilling were being written. Stock was being sold for an oil and gas company claiming leases on fifty thousand acres in Phillips, Lee, and Desha counties. The World Cotton Conference was coming to New Orleans from October 14 to 17 that year. Railroads were being built and the railroad companies rented land to store equipment and to pay for easements to build tracks.3 It was in this context of wealth and economic opportunity for the wealthy white men that the Elaine Massacre occurred.

Black Folks Were Doing Well

But south Phillips and north Desha county were also thriving for Black folks, just as Richard Wright had described. The two hundred Black landowners of Desha county in 1870 had been moving over the county line into Phillips County.

Isaac and Alminda Ferguson, a Black couple, owned land in Desha county in 1870. By 1900, they had moved to south Phillips County, where an almost all-Black town named Ferguson was founded. Isaac Ferguson served as postmaster there in 1900. There was a Black-owned Ferguson Gin and a store in the town – a whole community of Black landowners. This thriving Black community, growing and building in 1910, was perceived as a threat to the plans of the white landowners in Helena.

Due to discrimination by banks and financial institutions, most Black farmers seeking loans had to borrow from individuals. These individual lenders were, inevitably, your white neighbor or the landowner you were renting from. Scams were common. All through the last hundred years and more, there have been financial scams pushing Black people off their land. Some scams literally scared Black people off land. Some made it too difficult to be there. This is still happening today.

Members of the Pike, Jackson, Flenough, Scaife, and Hall families tell stories now, in 2023, of neighboring white owners moving land demarcations, planting or building on fields that are not theirs, letting livestock run loose to destroy crops. When the sheriff, mayor, clerk, courthouse, and judge were also not sympathetic, who could you trust to enforce your land ownership boundaries?

Ratio

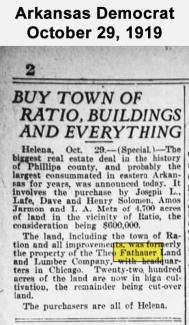

Copy from Arkansas Democrat, October 29, 1919 edition. Highlight added by Jennifer Hadlock.

Newspaper clipping from Arkansas Democrat, October 29, 1919, announcing the sale of land and buildings of the town of Ratio, Arkansas from the Theo Fathauer Land and Lumber Company to Joseph Lafe, Dave and Henry Solomon, Amos Jarmon, and I.A. Metz, all of Helena, Arkansas.

The town of Ratio, south of Elaine, is still easy to spot, because it has Gumwood Church, which is protected by huge Gumwood trees. There is a ditch there called Yellow Bank Bayou. The railroad used to pass through. But on October 1, 1919, Ocier Bratton, a white attorney, was arrested at Ratio for talking with Black farmers about how to sue for the money owed for their work, their crops, and for ginning their cotton. Ratio was the location of one of the first lodges of the Progressive Household and Farmworkers Union.4

In 1919, the land called Ratio was owned by Theo Fathauer of Chicago, who lived off Lake Shore Drive. In October 1919, less than two weeks after the massacre, Theo Fathauer re-did his will and sold his Ratio land, over 4,000 acres, to the Solomon brothers of Helena, and Amos Jarmon, the former sheriff. The newspapers called this the biggest land deal in Phillips County history.5

The land was later sold to Jesse Peter, who left the land to his sister, the poet Lily Peter. She fought to prevent chemicals from being used on her farm. She also fought the Army Corps of Engineers over some of the redirecting of rivers they attempted. Lily Peter employed three farm managers, Brooks Griffin, who was white and owned some land, and the Duncan brothers, two Black men related to some people who still live in Phillips County. When Lily Peters died in 1993, she left the farm to her nephew. That land ended up with Brooks Griffin.6

Today

Let’s bring this into the present. That same land called Ratio, formerly owned by Fathauer, then Peter, and which many Black people still in the area grew up living and working on, is the center which Griffin has amassed into an empire. The Griffins live in Nashville and Helena but have a giant plantation-style home in Ratio on the land, with a meticulously kept lawn. Since 2010, Griffin has sold over 30,000 acres to Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA), which has financially propped up and funded his amassing of more land. Griffin sold to an LLC called Global Ag Properties LLC for $158 million. Global Ag Properties LLC and Premiere Properties LLC is TIAA.7 TIAA is one of the largest landowners in the world. They claim to be a racially just organization and claim that they are feeding the world. But we know that most of what is growing in Phillips County today – soybeans (not edamame), corn (not for eating), and cotton – is not “feeding the world.” And the manner by which this land was acquired is not racially just by any means.

Moreover, the chemicals, the pesticides, used on this land, and the control of water in the area, are actually stopping local people from growing food, breathing clean air, and from having access to clean, sufficient water.

The current economic power structure here in Phillips County leads back to the time of the 1919 massacre. The current state of the land and schools and water serves to move poor and Black people out. Consider the high levels of herbicide and pesticide runoff into the water; these are not compatible with healthy human existence. Remember that the people who control the water control the area. Farming needs land and labor, but without water nothing will grow. The irrigation and flooding, combined with the chemicals, is effectively killing people. The large amounts of diesel and natural gas needed to power all the mechanically powered machinery to gin and cut and pick and truck and deliver and ship the soybeans, corn, rice, and cotton that is produced here is mind-boggling, and it is hurting people. Hundreds of wells have been drilled. There is almost no oversight of this. Even in the state of Mississippi there is more oversight of farm wells and of the elected levee boards there.

Recently there was a water boil order in Elaine and all the area south, because one pump operates for all in the area. The water system in Lakeview has had an ongoing off-and-on issue for the last few years, too. The Helena-West Helena water system failure made national news this year.

In the past, water was plentiful in Phillips County. Birds, bees, butterflies, frogs, creatures and fruit trees and vegetables abounded everywhere. People lived all over the county, working hard chopping cotton, not getting fair pay, but the water was clean, the food was good. The community was and is tight. Everyone knows each other or is related to each other.

The Helena Chemical Company, created here, is now part of a bigger agribusiness conglomerate.8 And the farmers here are reliant on the chemicals, even if they don't want to be; the only seeds that will grow are those resistant to the chemicals, because of chemical spreads.

The Cedar Chemical Company was shut down after proof of contamination of the surrounding soil and water. It is a superfund site.9

The introduction of big expensive farm machinery and the use of chemicals instead of workers to weed and defoliate began here in the mid-1950s when soybeans became a big money-making crop. This area also receives huge farm subsidies for big farmers.

An attorney from nearby Monroe County was on “60 minutes” for his plotting of subsidies. Deline Farm Partnership, which farms land owned by TIAA, is one of the biggest beneficiaries.10

Phillips County has the worst health statistics in the state of Arkansas. Lack of healthy food and the spraying of chemicals are connected to these statistics, and connected to each other.

A few people who do not even live here are making tens of millions of dollars, if not more, while destroying people, land, water, and air here. This needs to change. TIAA has the chance to lead on this by giving land back to the Black and small farmer, stopping chemical spraying and harmful farming practices, and funding community health, healing, and repair.

The long aftermath of the Elaine Massacre relates to these enduring legacies of white supremacy and racism, to the disregard for individual Black lives and the integrity of Black communities, to the relentless consolidation of capital and the poisonous exploitation of the natural environment. These factors are interrelated, and they are not accidental or incidental.

The truth matters.

Thank you.

This article is the text of the talk Jennifer Hadlock gave as part of a webinar sponsored by TIAA-Divest! and the Elaine Legacy Center, on October 26, 2023, sharing a small sample of her findings to date.

The article was subsequently published in the Arkansas Review, December 2023 issue. [Arkansas Review editor's note: The script of the October 26, 2023 web presentation has been edited slightly here for clarity and brevity.] Published on the Ending Racism USA website with permission of the author.

References

- Richard Wright, “Black Boy.” (1945), ch.2.

- Southern Alluvial Land Association, “Call of the Alluvial Empire”(booklet). (1919), pp. 7, 15.

- Missouri Pacific Railroad, “Missouri Pacific Railroad.” (1918) (Viewed in the Phillips County Courthouse Circuit Clerk’s Office.)

- Helena World, October 6-7, 1919. Also in O. S. Bratton to U. S. Bratton, November 5, 1919, Waskow Papers, University of Wisconsin.

- Arkansas Democrat, October 29, 1919.

- Annielaura M. Jaggers, “A Nude Singularity: Lily Peter of Arkansas, A Biography” (University of Central Arkansas Press, 1993); oral history, Duncan family; deeds in Phillips County courthouse and Will of Lily Peter.

- Arkansas Business, April 1, 2013 and Secretary of State LLC filing documents.

- Helenaagri.com/aboutus

- EPA. Superfund Site: Cedar Chemical Corporation, West Helena, AR Cleanup Activities.

- Robert Serio is an Arkansas lawyer who specializes in helping big farms maximize their payments from the Department of Agriculture. One of his clients – the Deline farming operations – has collected more than $21 million in subsidies since 2010 just on Phillips County land. CBS News, 60 Minutes: Why are hundreds of people in big cities receiving bailout money meant for farmers?